“In 1910 French chemist and scholar René-Maurice Gattefossé discovered the virtues of the essential oil of lavender. Gattefossé badly burned his hand during an experiment in a perfumery plant and plunged his hand into the nearest tub of liquid, which just happened to be lavender essential oil. He was later amazed at how quickly his burn healed and with very little scarring. This started a fascination with essential oils and inspired him to experiment with them during the First World War on soldiers in the military hospitals.”

If you’re in the aromatherapy biz, you are probably familiar with the story. The above version appears, word-for-word, on several websites, and the same basic tale on many. I’m fascinated by the appearance of “In 1910” in the story which, although true, is quite a recent development. There’s only one original source of that date: Monsieur Gattefossé, but whoever wrote the above clearly did not read Gattefossé’s own account. Ah well, that’s how it goes with rumours.

The story is basically correct, apart from the instinctual plunging of the hand into the nearest available liquid, which is total fiction. Anyway, who leaves large containers of lavender oil lying around unlidded? Certainly not a perfume chemist like Gattefossé.

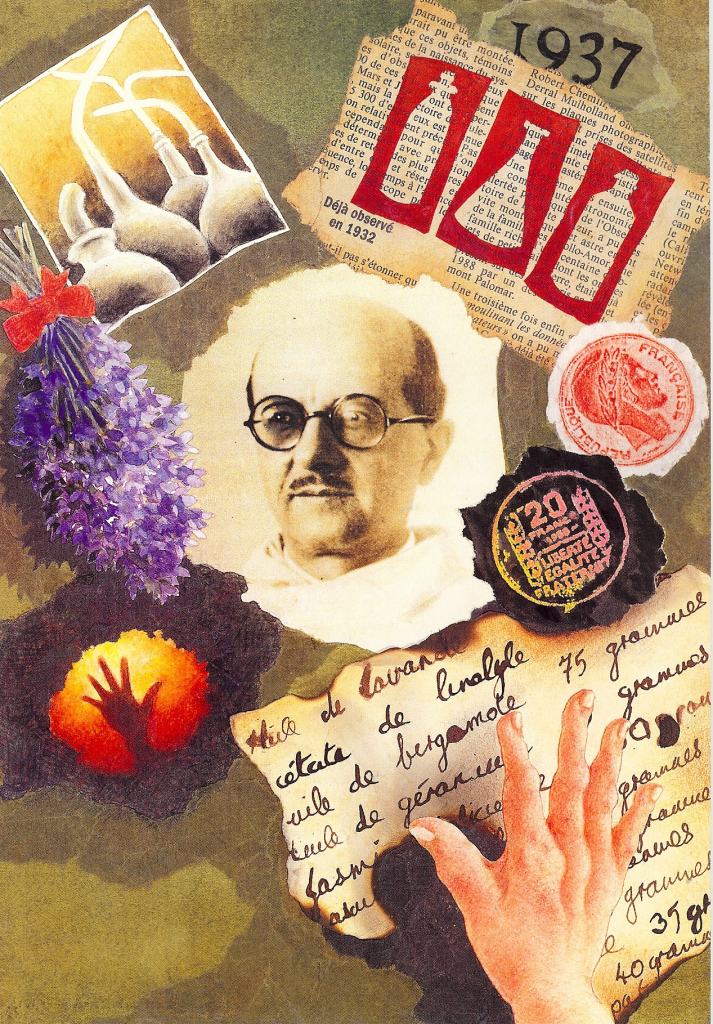

It’s remarkable how the mythical aspects of the tale have continued, long after the publication in English, in 1993, of his 1937 book Aromathérapie (by the way, this was the first appearance of the word “aromatherapy” in print). Yes, he burned his hand in his laboratory and yes, he treated it with lavender oil, but this was not a eureka-like, lucky-chance moment. It would be great if it was true. Translated from French, this is Gattefossé’s own description of the incident, and this is all he has to say about it:

It’s remarkable how the mythical aspects of the tale have continued, long after the publication in English, in 1993, of his 1937 book Aromathérapie (by the way, this was the first appearance of the word “aromatherapy” in print). Yes, he burned his hand in his laboratory and yes, he treated it with lavender oil, but this was not a eureka-like, lucky-chance moment. It would be great if it was true. Translated from French, this is Gattefossé’s own description of the incident, and this is all he has to say about it:

“The external application of small quantities of essences rapidly stops the spread of gangrenous sores. In my personal experience, after a laboratory explosion covered me with burning substances which I extinguished by rolling on a grassy lawn, both my hands were covered with a rapidly developing gas gangrene. Just one rinse with lavender essence stopped “the gasification of the tissue”. This treatment was followed by profuse sweating, and healing began the next day (July 1910).”

His application of lavender oil was clearly an intentional act, and the result impressed him greatly, and possibly saved his life. It was a special moment for him, and for aromatherapy.

Gas gangrene is a potentially fatal infection, and was the cause of many amputations and deaths in the First World War. Although traumatic gas gangrene is rare today, 25% of those who contract it still die. It is caused by infection of a wound, most commonly by Clostridium perfringens. Onset is rapid and dramatic (though it normally takes 1-4 days from the time of infection), with bacterial toxins causing tissue death and subcutaneous swelling and gas. Sweating is one of the early symptoms of infection. Since the bacterium is most commonly found in soil, Gattefossé’s rolling in the grass might have precipitated the infection.

While the incident did not initiate his study of aromatherapy, it was certainly a strong hint – a definite push in a direction he was already headed. Subsequently he collaborated with a number of doctors who treated French soldiers for war wounds using lavender and other essential oils. The accounts of these cases constitute a large part of his text.

Microbiological research shows that a number of essential oils are active against strains of Clostridium perfringens including winter savory (Satureja Montana) lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) lemon tea tree (Leptospermum petersonii) and tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia). Some of these are being given to factory-farmed chicken, which are susceptible to Clostridium perfringens-related disease. The essential oils don’t have the same drawbacks as antibiotics.

No-one has yet tested lavender oil against Clostridium perfringens, although we do know that lavender oil can inhibit the mechanism (known as quorum sensing) through which bacteria “decide” to release their toxins. Gattefossé’s use of lavender oil was not so much a happy accident as an instinctual success. It also helped make him famous, and we still remember the incident 101 years later. Serendipity, however you look at it.

References

De Oliveira TL, De Araújo Soares R, Ramos EM et al 2011 Antimicrobial activity of Satureja montana L. essential oil against Clostridium perfringens type A inoculated in mortadella-type sausages formulated with different levels of sodium nitrite. International Journal of Food Microbiology 144:546-555

Gattefossé R-M, Tisserand RB (ed.) 1993 Gattefossé’s aromatherapy: the first book on aromatherapy. CW Daniel, Saffron Walden, p 87

Shanmugavelu S, Ruzickova G, Zrustova J et al 2006 A fermentation assay to evaluate the effectiveness of antimicrobial agents on gut microflora. Journal of Microbiological Methods 67:93-101

Szabó MA, Varga GZ, Hohmann J et al 2010 Inhibition of quorum-sensing signals by essential oils. Phytotherapy Research 24:782-786

Wannissorn B, Jarikasem S, Siriwangchai T et al 2005 Antibacterial properties of essential oils from Thai medicinal plants. Fitoterapia 76:233-236

Thanks again for demystifying, this so well told, “urban aroma-legend”. Eager for the next one!!!

Thanks once again Robert. I’ve been going back and forth through some of my older books on the subject of aromatherapy (yours included of course) and I am finding all sorts of discrepancies and information being repeating verbatim from one book to another (I was taught that was plagiarism). Not yours or your wife’s, but mostly some of the newer books. Websites are even worse and its very difficult to find any aromatherapy information without having to look at lots of flashing ads, so another reason I find your blogs refreshing. This story of his burn was, as you said, repeated verbatim from one book to another and some books with different versions, none of which was correct as you have written here. I’ve read your translation of Gattefosse’s book and really also wanted to thank you for bringing aromatherapy to us here in the United States.

Robert, one statement strikes me as fiction: “both my hands were covered with a rapidly developing gas gangrene.” I have never heard of a bacterial infection that spread so quickly, so visible to the human eye. Perhaps you know more about gas gangrene and can enlighten me. Perhaps it does spread instantaneously, but it just seemed very odd to me.

Ann, I agree that websites are indeed worse than books. Misinformation can spread so rapidly. Most of those who do the spreading may not know that it’s wrong information, but if they don’t know any better it may come back to bite them.

Anya – I agree, and that’s why I mentioned that gas gangrene takes 1-4 days to develop, but at no point does Gattfosse clarify how much time passed between one event and the next. It sounds like it was all in a matter of hours, but maybe not.

What a great article! I have always wondered about this story – for exactly the reason you write – who leaves an open container of essential oil lying about? Thanks for clearing this up.

I appreciate your precise explanation of the true story. Also thanks for the laugh (in response to “large containers of lavender oil lying around unlidded”). Very funny.

Thanks Robert. The moment I first saw this myth I was too surprised. When I got myself wounded I did the same thing as the myth “placing on my wounds a spoonful lavender oil” and the heal didn’t come to immediate effect. Healing happened the next two or three days and I was required to put neat lavender oil onto my injury continuously to take the healing process to the max. This proves that healing isn’t a one-day Cinderella story. And all written works are prone to exaggeration.

cheers ~ Natski Y

Thanks Robert!! is it also true if you read the French version, that much of his work was done with terpeneless oils? can you remind me and elaborate on that? just catching up to your fabulous blogs/papers here! Thanks again

Sylla

Gattefosse believed that monoterpenes were very strong irritants, and he therefore labelled them as being toxic. Almost all his work with lavender was carried out with deterpenated lavender oil (lavender contains only 2-10% of monoterpenes). Because monoterpenes are inflammable, he believed that they could oxidize very rapidly, and I think here lies his confusion. Bursting into flame when heated should not be confused with auto-oxidation, a very much slower process. The oxidation of monoterpenes does happen and is not desirable, but it takes months or years, and can easily be prevented with antioxidants, and/or by keeping oils cool. Monoterpenes have some very useful properties which G. was not aware of. I don’t think it makes any difference whether you read the French or English version.

Hi just found your site and loved your article, wondering if you could comment on Gas Chromatatography (I think) testing of oils for medicinal quality assurance. Have been told that there are different grades of oil and depending how they are processed will lose their healing qualities and be good for perfume, or food grade. Thank you again for your information

Hi Elizabeth,

Yes, gas chromatography (GC), along with mass spectroscopy (MS) is the go-to method for evaluating an essential oil for purity / adulteration. GC/MS determines the proportion of individual constituents, and adulterants will show up, if you know what to look for.

Grades – there are pharmaceutical grades (BP or USP) for a few essential oils (mostly used for making medicines taste better) and there are food grades (FCC), intended for the use of essential oils as food flavorings. A few companies claim to sell a ‘Therapeutic grade’ but there is no such standard, nor is there a ‘perfumery grade’. There are ISO (International Organization of Standardization) standards for many essential oils, and these are widely used in the essential oil industry.

Essential oils will lose their healing qualities if they are allowed to oxidize. Citrus oils are the most prone to oxidation.

Hi Robert,

Quick question on the oxidation re: citrus oils. Is this what makes then especially reactive to plastic? I ask because I have a diffuser which has the plastic bowl to put water and EO in, and was advised not to use citrus as it would corrode the plastic quickly over time.

Really enjoyed the article! Never heard of this story. Loved reading it!

Hi Karlie, over time most essential oils will eat away at most plastics, but only if they are undiluted. It does depend on the type of plastic. As far as I know, citrus oils are not especially potent in this regard. They are very good solvents for cleaning, as are pine oils, but I have seen clove oil, tea tree oil and others eat plastic.

Hi Robert I hope you are doing well. I would like to understant better about “nature identical” some essential oils supliers do sell their products as true aromatherapy, but we can read in some labels of their products “nature identical” what that really mean, could you please explain it. Thanks for your attention

Hi Vera,

I don’t know where you have seen ‘nature identical’ – I have only seen it on some wholesaler lists of essential oils, though they more commonly use ‘reconstructed’. When applied to an essential oil, it means that various single aroma chemicals have been blended to create something similar to the natural oil. ‘Nature identical’ is often found on food labels, but it would be more correct if it was ‘nature-similar’!

Each time I read that story whether online or one of the several aromatherapy books, I questioned why would one dip his hand into a vat of unknown liquid especially a scientist. I’ve experienced lavender, not the eo, an infusion, on burns and know the healing that takes place so I gave the story merit. Thank you so much for setting this record straight sharing the link on Facebook.